Product theory is full of competing commandments. “Build an MVP.” “Cross the chasm.” “Disrupt yourself.” “Bundle or unbundle.” Product managers, founders, and leadership in general, juggle them, quoting whichever one fits the current deck. The theories are great: most are drawn from empirical evidence.

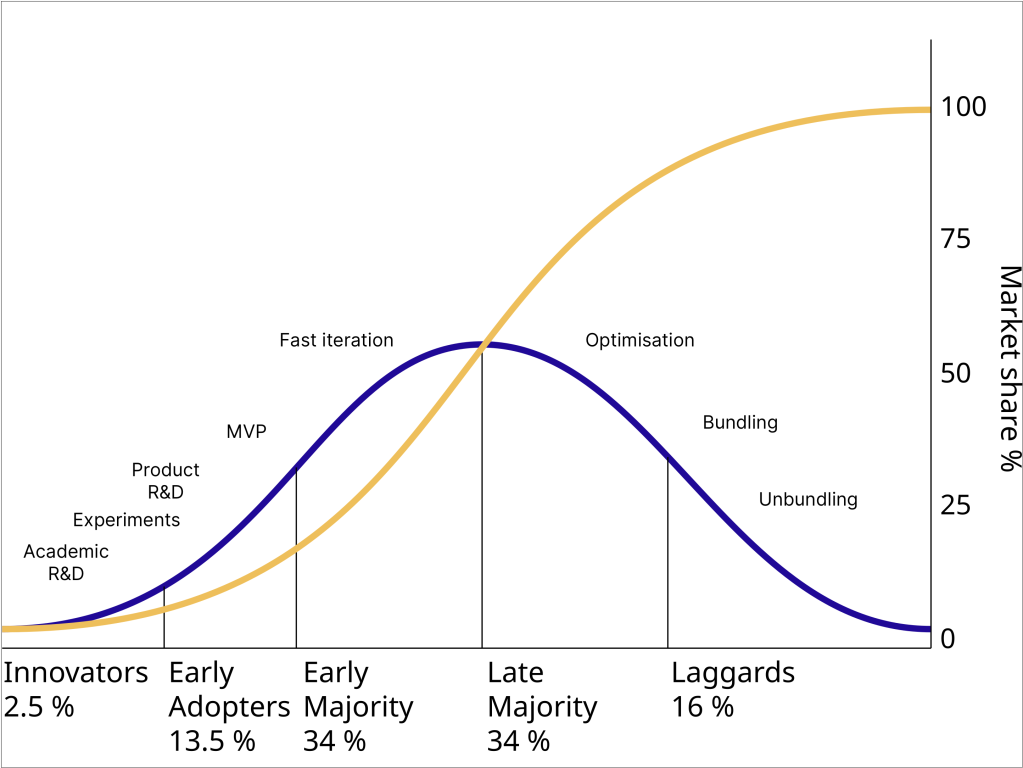

A problem I noticed in time is that we treat them as stand-alone. I believe, in reality, they’re just milestones on one curve: Everett Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation.

Innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, laggards — the shape is familiar, a Bell curve.

“Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated over time among the participants in a social system” says the observer of this phenomenon, Everett Rogers. An old thing hailing from 1962! Still holds. That diffusion curve isn’t just sociology; it’s a product compass. Each stage of the curve makes a different product strategy valid. Misapplying them out of place can doom great products, despite good execution.

⸻

Experiments and R&D → Innovators

At the very left, there is no “market.” Here there be only innovators — the few who adopt for curiosity’s sake. This is where experiments and academic R&D belong. Throwing products at this zone is malpractice. Paraphrasing someone famous, the purpose of invention is learning. You don’t need MVPs here. You need experiments, often ugly, often useless in market terms, but generative.

Google X embodies this. Projects like Loon or self-driving cars weren’t products; they were hypothesis engines. Innovators engaged because they wanted to explore. The congruence worked.

Juicero didn’t see it like that. It took what was effectively a food-supply experiment and launched it as if the early majority were waiting. The mismatch: users were still innovators of cold-pressed juice supply chains, but Juicero used a product strategy fit for optimisation and scale. The result was ridicule and collapse.

At this stage, launches are dangerous. Each one ratchets expectations. Too many “launches” of half-science and the market stops taking you seriously. There may be such a thing as launch debt: the erosion of trust capital with every premature reveal.

⸻

MVP → Early Adopters

Once an idea turns into a possibility, it enters the product R&D and MVP stages. In the lean startup it’s called “that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning with the least effort”. MVPs are for early adopters — people willing to tolerate roughness in exchange for vision. At this stage of innovation diffusion it’s about testing hypotheses with customers, not satisfying demand.

Tesla’s Roadster was exactly that. An overpriced, jury-rigged sports car, it wasn’t meant for scale. It was meant for believers. Those early adopters gave Tesla data, legitimacy, and patience. The alignment, perfect: MVP strategy with early adopter audience.

Fisker Karma? The exact opposite. It launched as though the early majority were ready for electric luxury sedans. But reliability was catastrophic. The mismatch: users were early adopters of EV tech, but Fisker treated them as a late-majority market expecting optimisation. Trust imploded.

Tesla framed its Roadster as a stepping stone but Fisker sold the Karma as a revolution already past.

⸻

Fast Iteration → Early Majority

When a product tries to leap into the early majority, it goes through the famous dangerous place, coined by someone named Geoffrey Moore: The Chasm. Pragmatists don’t care about your vision. They want a safe bet. The only way across is visible, relentless iteration. Fast iteration is as essential for success as a YouTube thumbnail’s weird facial expressions and pointing fingers.

Amazon Web Services nailed this. EC2 launched with bare-bones compute, but the drumbeat of new instance types, storage, and networking every quarter reassured customers. The strategy was congruent: fast iteration for an early-majority audience. The pace itself created confidence.

HP Cloud stumbled. It entered the same market but rolled out features at a glacial pace. Worse, it packaged itself as a mature bundle. The mismatch: users were early majority of cloud compute, but HP approached them with bundling and optimisation. Customers defected to AWS before HP could close the gap.

Iteration here isn’t just product. It’s messaging, onboarding and support. For this to work, commitment is key. Commitment of people, cash, risk, loss. But the chasm IS a dangerous place after all.

⸻

Optimisation → Late Majority

Once adoption tips, the late majority arrives. Their demand is stability, price, reliability. In a book from the previous century it says “Disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously”. But at this stage of diffusion the opposite is needed, sustaining technologies. The optimisations, are what the late majority values. You’re no longer trying to prove the product works. You’re trying to prove it scales.

AWS again provides the yes. By the 2010s, it turned its energy to cost reduction, enterprise compliance, and reliability. Optimisation strategy for late-majority users.

Webvan shows the no. It invested billions into optimised logistics — warehouses, fleets, automated systems — but grocery delivery itself was still in MVP territory. The mismatch: users were early adopters of online grocery, but Webvan acted as if they were late majority demanding optimisation. The infrastructure collapsed under lack of demand.

Optimisation also means operational trust. The late majority wants compatibility and enterprise support.

⸻

Bundling → Maturity

At saturation, innovation slows. Commodities emerge. A supple and nice line from the COO of a long sunset company says: “There are only two ways to make money in business: one is to bundle; the other is unbundle.”. Maturity is bundling time.

Adobe got this right. Photoshop, Illustrator, Premiere — individually powerful, but together irresistible as Creative Cloud. Users were late-majority creatives; bundling gave them convenience and predictability.

Google+ got it wrong. It tried to bundle messaging, social graph, photos, and video before it had won any one product. The mismatch: users were early adopters of online identity, but Google+ deployed a bundling strategy fit for maturity. Nobody wanted the bundle.

⸻

Unbundling → Renewal

When bundles calcify, resentment brews. That’s when unbundling strikes. We host a famous blog with a whole concept dedicated to Bundling and Unbundling. It shows the history of the technology industry has been one of bundling and unbundling in turn. Unbundling is often how disruption sneaks in.

Slack is the yes. It unbundled team communication from the bloated email bundle. Users were maturity-stage email sufferers; unbundling gave them relief.

Yahoo is the no. It resisted unbundling, stuffing news, chat, search, groups into a portal that tried to be everything. The mismatch: users were maturity-stage web users hungry for unbundled excellence, but Yahoo doubled down on bundling. The portal rotted.

Unbundling works because mature bundles calcify. Customers resent paying for bloat they don’t use. New entrants exploit that resentment by stripping to essentials. Like say … make a blog out of markdown files only, and a whole website out of souped up JavaScript. Or host static sites like it’s my childhood.

⸻

A Tool to Check Against

So what’s left is not theory, but alignment. The innovation stage tells us which playbook to run. Fail to match them, and the market will fail us.

Here’s a simple self-test:

- Am I calling this an experiment when users expect a product?

- Am I shipping an MVP to pragmatists who expect reliability?

- Am I iterating when users want optimisation?

- Am I optimising before adoption proves demand?

- Am I bundling without a single market win?

- Am I clinging to bundles while customers are peeling away?

⠀

If we answer “yes” to any, we out of sync with the curve. Each of the product strategies are valid, but only if the core innovation of the product is in a diffusion stage that matches correctly. The diffusion is slow and patient. There is time even for mistakes, but wait enough and it punishes mismatches quite badly.

Leave a Reply